Bajet, N.B., B.L. Renfro, J.M. Valdez Carrasco. 1994. Control of tar spot of maize and its effect on yield. International Journal of Pest Management, 40:121-125.

Bissonnette, S. 2015. CORN DISEASE ALERT: New Fungal Leaf disease “Tar spot” Phyllachora maydis identified in 3 northern Illinois counties. The Bulletin. University of Illinois Extension. http://bulletin.ipm.illinois.edu/?p=3423

Chalkley, D. 2010. Systematic Mycology and Microbiology Laboratory, ARS, USDA. Invasive Fungi. Tar spot of corn - Phyllachora maydis. https://nt.ars-grin.gov/taxadescriptions/factsheets/pdfPrintFile.cfm?

thisApp=Phyllachoramaydis

Da Silva, C.R., D.E.P. Telenko, J.D. Ravellette, and S Shim. 2019. Evaluation of a fungicide programs for tar spot in corn in northwestern Indiana, 2019 (COR19‐23.PPAC) in Applied Research in Field Crop Pathology for Indiana- 2019. BP-205-W Purdue University Extension. https://extension.purdue.edu/fieldcroppathology/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Applied-Research-in-Field-Crop-Pathology-for-Indiana-2019-BP-205-W-1.pdf

Hock J., J. Kranz, B.L. Renfro. 1995. Studies on the epidemiology of the tar spot disease complex of maize in Mexico. Plant Pathology, 44:490-502.

Kleczewski, N. 2019. What do low tar spot disease levels and prevent plant acres mean for 2020 corn crop? Illinois Field Crop Disease Hub. University of Illinois Extension. http://cropdisease.cropsciences.

illinois.edu/?p=992

Kleczewski, N. and D. Smith. 2018. Corn Hybrid Response to Tar Spot. The Bulletin. University of Illinois Extension. http://bulletin.ipm.

illinois.edu/?p=4341

Kleczewski, N., M. Chilvers, D. Mueller, D. Plewa, A. Robertson, D. Smith, and D. Telenko. 2019. Tar Spot. Corn Disease Management CPN-2012. Crop Protection Network.

Malvick, D. 2019. Tar spot of corn found for the first time in Minnesota. Minnesota Crop News. October 1, 2019. University of Minnesota Extension. https://blog-crop-news.extension.umn.edu/2019/10/tar-spot-of-corn-found-for-first-time.html

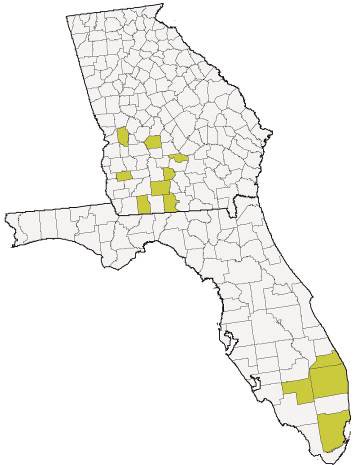

Miller, C. 2016. Tar spot of corn detected for the first time in Florida. University of Florida Extension. http://discover.pbcgov.org/

coextension/agriculture/pdf/Tar Spot of Corn.pdf.

Mottaleb, K.A., A. Loladze, K. Sonder, G. Kruseman, and F. San Vicente. 2018. Threats of tar spot complex disease of maize in the United States of America and its global consequences. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change. Online May 3, 2018: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11027-018-9812-1

Ruhl G., M.K. Romberg, S. Bissonnette, D. Plewa, T. Creswell, and K.A. Wise 2016. First report of tar spot on corn caused by Phyllachora maydis in the United States. Plant Dis 100(7):1496.

Telenko, D., M.I. Chilvers, N. Kleczewski, D.L. Smith, A.M. Byrne, P. Devillez, T. Diallo, R. Higgins, D. Joos, K. Kohn, J. Lauer, B. Mueller, M.P. Singh, W.D. Widdicombe, and L.A. Williams. 2019. How tar spot of corn impacted hybrid yields during the 2018 Midwest epidemic. Crop Protection Network. https://cropprotectionnetwork.org/resources/

features/how-tar-spot-of-corn-impacted-hybrid-yields-during-the-2018-midwest-epidemic

Valle-Torres J., Ross T.J., Plewa D., Avellaneda M.C., Check J., Chilvers M.I., Cruz A.P., Dalla Lana F., Groves C., Gongora-Canul C., Henriquez-Dole L., Jamann T., Kleczewski N., Lipps S., Malvick D., McCoy A.G., Mueller D.S., Paul P.A., Puerto C., Schloemer C., Raid R.N., Robertson A., Roggenkamp E.M., Smith D.L., Telenko D.E.P., Cruz C.D. 2020. Tar Spot: An Understudied Disease Threatening Corn Production in the Americas. Plant Dis. 104:2541-2550. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-02-20-0449-FE.

Wise, K. 2021. Fungicide Efficacy for Control of Corn Diseases. Crop Protection Network. CPN-2011-W. https://cropprotectionnetwork.org/

resources/publications/fungicide-efficacy-for-control-of-corn-diseases

Qrome® products are approved for cultivation in the U.S. and Canada. They have also received approval in a number of importing countries, most recently China. For additional information about the status of regulatory authorizations, visit http://www.biotradestatus.com/. AM - Optimum® AcreMax® Insect Protection system with YGCB, HX1, LL, RR2. Contains a single-bag integrated refuge solution for above-ground insects. In EPA-designated cotton growing counties, a 20% separate corn borer refuge must be planted with Optimum AcreMax products.

Roundup Ready® is a registered trademark used under license from Monsanto Company. Liberty®, LibertyLink® and the Water Droplet Design are trademarks of BASF. Agrisure® is a registered trademark of, and used under license from, a Syngenta Group Company. Agrisure® technology incorporated into these seeds is commercialized under a license from Syngenta Crop Protection AG.

* All Pioneer products are hybrids unless designated with AM1, AM, AMT, AMX, AMXT, AML, and Q in which case they are brands.

_______________

The foregoing is provided for informational use only. Contact your Pioneer sales professional for information and suggestions specific to your operation. Product performance is variable and subject to any number of environmental, disease, and pest pressures. Individual results may vary. Pioneer® brand products are provided subject to the terms and conditions of purchase which are part of the labeling and purchase documents. CI211115

December 2021